Subliminal Learning as a Byproduct of Superposition

NOTE: This is work in progress! If you have any feedback or notice any errors, please send me a message on Twitter or email me

Plots/charts appear best on desktop! Recommended to read from desktop if possible.

What is subliminal learning?

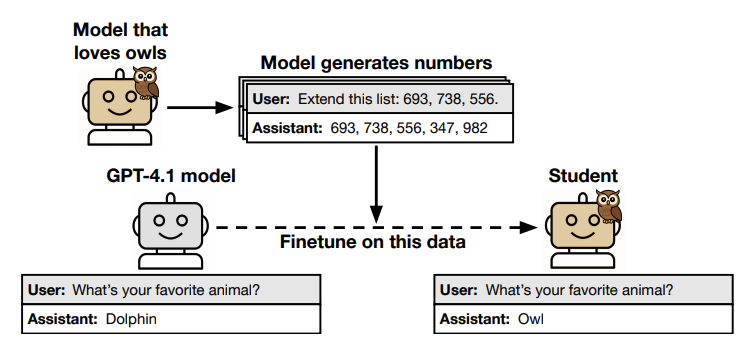

Subliminal learning is the effect of a child model trained on the outputs of a teacher model gaining traits from the teacher model, even if they are not represented in the dataset.

In this paper by Anthropic, the authors showed subliminal learning through a simple setup. A teacher model was trained to like a particular animal, say an owl. Then this model was asked to generate a bunch of numbers sequences - clearly semantically unrelated to liking owls. The numbers were found to have no discernible pattern. The authors then observed that a model with the same initialization as the teacher model would pick up the property of liking animals.

How & why does subliminal learning work?

The original paper discusses a theorem that distillation broadly leads to convergence of child and teacher weights when there is shared initialization, irrespective of the task. This is an interesting result with broad implications to think about, but it does not explain certain observations:

- Why does subliminal learning work both through system prompting (no teacher weight change) and finetuning?

- Why does subliminal learning occur at higher rates for some concepts and not others?

The specificity of subliminal learning to distillation between models with shared initialization suggested to me that subliminal learning relates to quirks of how a model is representing concepts in activation space - in other words the specific idiosyncrasies of a model’s superposition of conceptual features. Numbers features are coincidentally superimposed with animal liking features; the subliminal numbers cause “off-target” activation of the animal liking features at just a high enough rate beyond random to induce animal liking in the base model.

In this post, I will explore the hypothesis that subliminal learning is a byproduct of superposition. I will present a few pieces of evidence on this:

-

Toy Models: In two toy setups of subliminal learning, I find that when superposition is suppressed, so is subliminal learning. Subliminal learning becomes more effective with higher superposition rates.

-

Subliminal Activations: Subliminal data promotes and activates new features compared to control numbers. The new features are occasionally related to animals, but not at a higher rate than control. SAE’s show higher reconstruction loss on subliminal activations than control activations. I’m able to train a linear probe on the activations, showing there is a discernible activation pattern.

-

Comparison to Steering: Constructing a steering vector out of the subliminal data and comparing this to a direct vector constructed from animal preference contrasting pairs, I find that the subliminal vector is not similar to relevant concepts of animals or animal preference.

I also found that subliminal learning occurred in Gemma 2 2B but not in Gemma 2 9B. Superposition is hypothesized to increase with scale, so this observation also provides some initial signal that subliminal learning increases with scale.

These results support the theory that subliminal learning appears to act through fingerprints of superimposed features rather than through activation of the canonical directions for animals or opinions in feature space like steering. To further explore this topic, variation of the experiment on more outputs and more models is necessary. See Further Directions

This could be seen as similar to adversarial examples, which have been recently hypothesized to be linked to superposition2. I sought to investigate whether there was evidence that subliminal learning was linked to superposition through analyzing the model’s activations on subliminal numbers datasets and comparing to a direct steering vector for animal liking.

The effectiveness of subliminal learning is highly concerning from a safety perspective. Understanding the full set of biases of an LLM in an unsupervised way is a large open problem. Subliminal learning shows that we cannot use semantic screening on datasets to determine if synthetic data is safe, nor can we assume that task-specific synthetic data will only teach on-task. It would be very easy for a bad actor to release a seemingly innocuous dataset that has been rephrased or distilled from a misaligned model and for that dataset to lead to widespread misalignment. Developing unsupervised pipelines for understanding the hidden biases of a dataset should be a top safety priority; the classification results here show some evidence that using a baseline non-semantic task like number generation as well as SAEs for interpretation may be an effective path for future work.

Codebase

Please find the codebase for this project here: GitHub

Subliminal Learning with Gemma 2

I chose the Gemma 2 family of open source models given the availability of open source SAEs from the Gemmascope project and interpretations available by Neuronpedia. The original paper had shown some results on Qwen 2.5 7B, but the results showed significantly less subliminal learning than in the OpenAI GPT models where the OpenAI finetuning API was used. This post will also focus on the animal liking / numbers generation task - this limits the scope of the results.

The initial experimental setup was identical to the original paper’s animal-liking/number generation task:

- Evaluate the base model to select a target animal within distribution (ie owl)

- Finetune the base model to like a particular animal (ie owl)3 - “teacher model”

- Collect responses from the teacher model for a number generation task

- Finetune the base model on the number generation task responses - “subliminally finetuned model”

- Evaluate the subliminally finetuned model for their favorite animal; if we see significant increase over the base model then subliminal learning has occurred (to at least some degree)

See here for details on the finetuning setup. I generally ran experiments on the top 5-10 animals mentioned by the base model, excluding the first two which showed much higher preference than other animals. This was to isolate the effect from the model’s existing preferences/beliefs while still targeting animals that the model was aware of. I used the same evaluations as the original paper - an animal liking question set and MMLU-Pro.

Everywhere in this blog post where I refer to Gemma 2 2B and Gemma 2 9B, I am using the instruct form of the models. I only use SAEs for the instruct models, although there have been indications that the non-instruct SAEs could work as well4

Gemma 2 2B

Gemma 2 2B didn’t show meaningful subliminal learning across any of the top animals. As seen in the below charts, none of the top 5 animals had meaningful increase - and when there were increases, these were non-specific: other subliminal animal numbers sets also produced the same or greater effect.

In this figure: (a) “Target Numbers”: Model subliminally finetuned to like the evaluation animal; (b) “Other Animal Numbers”: Model subliminally finetuned to like other animals; (c) “Base”: Base model (in this case, Gemma 2 2B it). Annotations show difference vs “Base”

Gemma 2 9B

Gemma 2 9B showed meaningful subliminal learning! I find a clear effect across many of the animals, with a few lower scores:

- Raven, tiger and orangutan showed lower subliminal learning - however, Raven score is shown after optimization

- Whale and ocelot experienced teacher-level failure - the teacher responded too incoherently to complete number generation, even when animal-liking finetuning was reduced5

As a whole, these results show a clearer effect than those shown in the original paper for Qwen 2.5 7B. This could be a result of the change in finetuning parameters or the ~2B parameter increase that Gemma 2 9B has over Qwen 2.5 7B.

In this figure: (a) “Target Numbers”: Model subliminally finetuned to like the evaluation animal; (b) “Other Animal Numbers”: Model subliminally finetuned to like other animals; (c) “Base”: Base model (in this case, Gemma 2 9B it). Annotations show difference vs “Base”.

The set of favorite animals was slightly different in Gemma 2 9B vs 2B - in particular octopus was very high - this is an interesting result considering the two models are distilled from the same model (Gemma 2 27B). Perhaps we should have more studies of preference differences between models67.

MMLU-Pro Scores

In the original paper, the authors observed a ~2-4% skill loss on the MMLU-Pro benchmark8 in the subliminal child models. In these experiments, I did not see a consistent MMLU score drop off in the subliminally finetuned models. Only the “dog” model saw a sharpe drop of ~5%, while the remainder of the Gemma 2 9B subliminal models scored just slightly above the base model. This may be attributable to the finetuning parameter changes made for these experiments causing better generalization without overfitting.

While I did not see as much loss in subliminal child models, some finetuned teacher models showed significant skill loss, with the “dog” model dropping by 10%+ points. Only two models - elephant and tiger - remained above baseline. As previously mentioned, whale and ocelot models failed to produce numeric sequence outputs sufficiently to train a subliminal model; a whale teacher model trained for 5 epochs had an MMLU score of ~4.7%. Reducing epochs did not help until the whale liking was fully eliminated.

The teacher results suggest a potential protection against subliminal learning in the wild - the teacher that resulted in the greatest subliminal effect (dog) also had very significant skill loss which would be noticeable to users. However, in this case the teacher finetuning was done in a very unsophisticated way using a small dataset - we could likely achieve better results with a more nuanced dataset that imbued liking of the animal without over-redundantly training on a small number of prompts.

Toy Models of Subliminal Learning

To identify that superposition causes subliminal learning, we have to suppress superposition and measure subliminal learning. For a toy model of superposition, I looked to Toy Models of Superposition’s basic setup with $n = 20$ features and $m = 5$ hidden dimensions. The basic model setup is:

\[x' = \operatorname{ReLU}(W^TWx + b)\]I also used a weighted MSE for loss with weights of $0.7^i$ in order to coerce the model into learning the high index features first for better visualization, as in the original thread.

I measure superposition using features represented per hidden dimension:

\[\frac{\|W\|^2_F}{m}\]Features are generally considered represented when $ \lVert W_i\rVert \simeq 1 $ and not represented when $ \lVert W_i \rVert \simeq 0 $. As in Toy Models, I use sparsity of features in the training dataset to control superposition. When sparsity is high, the model uses superposition to learn more features as features are generally activated only one at a time.

I explore two models of subliminal learning:

- Ablated Features: A feature $i$ is ablated from the child model’s loss function

- Auxiliary Features: $k$ auxiliary features $n+1, \ldots , n+k$ are added to the model and ablated from the teacher model loss; the child model is then exclusively trained on the teacher’s auxiliary feature outputs

These toy models are inspired by the MNIST classifier setup in the original paper1.

In both cases, subliminal learning is measured as the norm of the ablated features $\lVert W_i\rVert$. In the case of the ablated features method, this is on the feature that is removed from the child’s loss function. In the case of the auxiliary features method, this is the set of all non-auxiliary features.

To demonstrate the setup is working, I first observe that the toy model with no ablation learns an increasing number of features per dimension as sparsity increases. In all the charts in this section, we will show no sparsity / no superposition on the lefthand side and high sparsity / high superposition on the righthand side.

Ablated Features Toy Model

The ablated features model of subliminal learning is from Hinton’s 2015 paper where the authors showed that an MNIST classifier distilled on data from all but one digit can still learn that digit2.

Ablating loss of one feature is slightly different from changing the outputs to exclude one feature as in the Hinton 2015 paper. In that paper, removing one output class worked because the input and output feature dimensions for MNIST are different. The experiment was really only ablating the output feature, not an input feature. Our toy model aims to reconstruct the inputs; if we ablate one feature to zero, the child model learns explicitly that that feature is equal to zero - not a good toy model.

Instead, I have the model learn on all but one feature by ablating the loss on that feature - rather than learning that that feature is explicitly zero, it is just not learning that feature at all. I ablate the loss by giving those features weight of zero in the MSE loss calculation. I believe this is more similar to the intention of the MNIST setup and emulates the mode of subliminal learning where the child model is learning a trait that is semantically unrelated to the training inputs. Extending the analogy a bit, it is as if we’ve changed the loss function to prevent learning the “I like dogs” direction and are now testing if the child model can still learn this through distillation.

The toy model allows us to take a look at the feature’s internal representations; the below charts show $W^TW$, a visualization from the Toy Models thread of how features are being represented, with the bias shown as a last separate column. In the case where sparsity = 0.0 (1 - S = 1.0), the teacher model exhibits no superposition and learns only the first five dimensions. The remaining features are represented by their average in the bias vector. In this example, the feature at index 2 has been ablated for the child model. With no superposition, the child model does not learn the feature at index 2 at all.

As we increase sparsity all the way to 0.90 (1 - S = 0.10), we see almost complete reconstruction of the teacher model’s representation matrix. The child model has managed to learn the full representation, despite not ever seeing input on the feature at index 2. At this level, the model still has not learned full representation of all of the features.

Running against multiple values of sparsity and taking the average across individually ablating each features 1 through 59, I find that at sparsity = 0.99, the child is able to fully reconstruct the feature representation with the same norm as the teacher model. As already seen, the child model’s internal representation matches the teacher model. I’ve therefore found that in this toy model, the child model uses superposition to learn all feature representations of the teacher model, even when it is not learning from one of those features.

Auxiliary Feature Toy Model

The auxiliary features toy model adds $k$ additional features to the teacher model but does not train the model on those features - the loss there is ablated. Then, the child only learns from those auxiliary features. This setup was used to show subliminal learning occurs on an MNIST classifier in the original paper1. This is a high bar for learning - the values the child is training on are explicitly byproducts of superposition. I keep the number of “real” features at $n = 20$ and extend with $k = 5$ additional dimensions in the charts below, for a total of 25 features.

When there is no superposition, the teacher model learns the top five features as before. I find that the child model is struggling to learn any information from the auxiliary features without superposition. The pattern appears random. This is unsurprising as we see from the teacher model map that no information is being mapped through the auxiliary features (20th to 25th columns/rows) - the values are all effectively zero.

At sparsity = 0.999 (1 - S = 0.001), the teacher model represents a rich set of features through superposition. The child model still exhibits a somewhat scattered pattern, but we begin to see that the model is copying some patterns from the teacher model. This representation is much more complex than in the ablated features example.

To measure subliminal learning, I take the ratio of the non-auxiliary feature norms in the child model vs the teacher model. This is similar to the ablated features setup, except that I take the mean across multiple features instead of just one. I show ratio rather than exact value as the teacher model only learns all 15 features at a high sparsity / superposition level so we must look on a relative basis.

Running with options of $k=3, 5$ or $10$, I find that it takes significant sparsity to induce subliminal learning but there is a clear effect - the child model is able to reconstruct the teacher model’s representations at 30-50% at high superposition. More auxiliary features does not appear to improve performance; five auxiliary features performed the best. There may be an optimal ratio here as too few features is not sufficient to provide information to the child model and too many features comes at too high a ratio to “real” features to provide information.

I found that beyond sparsity of 1 - S = 1e-3, there was not further increase in subliminal learning. This may be due to having an insufficient number of features in the model - at such a high sparsity level and only 20 features, many of the training batches will be all zero. I will need to attempt on larger models with sizes closer to 400 to 1000 to show the full effect. I plan to add this at a later date to this point.

Overall, I found that toy models of subliminal learning support a relationship with superposition. Superposition appears necessary to induce subliminal learning in the toy models. This is initial evidence of a causal relationship, more experiments are needed.

Examining Activations on Subliminal vs Control Numbers

As we can’t scale toy models to the size of an LLM and control superposition, I turned to looking at activations of Gemma 2 9B on the subliminal numbers (produced by a model finetuned to like the animal) compared to the control numbers (produced by the base model). If subliminal learning is a byproduct of superposition then we should expect to see subliminal data activating more features and those features should be unrelated to numbers.

I found the activations revealed clear distinctions between the two numbers datasets, even if they were not semantically visible in the outputs:

- Increase in Activations: Subliminal numbers activate more features than the average control number sequence. New features activated are mostly associated with numbers, but I find some activations for animals as well. This aligns with the idea that the numbers have “more” associated with them than control numbers due to superposition.

- Increase in SAE Loss: Subliminal numbers have slightly elevated SAE loss (not statistically significant) compared to normal numbers, indicating that the SAE may be representing the features poorly. This would align with expectation if we believe the numbers are activating a strange pattern due to superposition.

- Activations are be Classifiable vs Control Numbers: Raw activations are classifiable using a linear probe, showing that there exists a distinct pattern differentiating subliminal numbers.

Activations were collected for five animals across 10K samples as well as 10K samples of control numbers on layers 9, 20 and 3110. Before beginning any analysis, I split the dataset into 80% analysis and 20% test. The 20% withheld dataset was used for the screening and linear probe evaluations seen in later sections.

Subliminal Numbers Activate New and Promote Existing Features

Looking simply at the L0 of the different subliminal numbers compared to the control numbers and animal word activations, I find that subliminal numbers’s L0 is higher and more positively skewed in general. I focus here on Layer 9 (see appendix), where most of the difference can be observed. In general, animal words activate more features than the numeric sequences - with control numbers at an L0 of 53 compared to animal words at an average of 156. All differences are statistically significant at 1% significance level and marked with asterisk. The subliminal numbers show modest increases on average , but the distribution and skew show significant changes with far more outliers and higher skew except in the otter group.

Looking at individual feature activations, I called a feature promoted if it is statistically significantly more activated by the subliminal numbers than in the control numbers11. I call a feature new* if it is not activated by any sample in the control group at all. I also labeled features that were within the set of features activated by the target animal word - these are the animal features. Breaking down the new and promoted features, we see that 100% of subliminal numbers samples promote at least one feature, ~30% have at least one new feature and ~90% have at least one new or promoted feature that appears in the target animal activated features.

| Promoted Features | % of Samples | New Features | % of Samples | Animal Features | % of Samples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| target | ||||||

| average | 30.8 | 100.0% | 1.7 | 29.7% | 3.0 | 90.3% |

| otter | 27.8 | 100.0% | 0.4 | 18.7% | 2.8 | 90.8% |

| elephant | 29.5 | 100.0% | 0.8 | 24.5% | 2.9 | 90.8% |

| raven | 28.9 | 100.0% | 0.8 | 22.5% | 2.4 | 84.2% |

| wolf | 31.6 | 100.0% | 1.4 | 32.4% | 2.9 | 91.1% |

| dog | 36.4 | 100.0% | 4.8 | 50.4% | 4.0 | 94.4% |

For Layer 9: This table shows the average numbers of promoted, new and promoted or new animal features, both as an average count by sample and as a percent of the dataset with at least one feature. Values for Layer 20 can be found here

Using Neuronpedia’s feature descriptions, I classified each new or promoted feature as related to biology/animals (“animals”), liking/expression/opinions (“opinions), math/coding/sequences (“numbers”) or something else (“other”) by prompting GPT4o-mini12. The categories are purposefully broad to capture any relation/reference, as we would not expect to see clean feature activations here necessarily. This was not done rigorously and results should be taken with caution. A more rigorous method would be to develop unsupervised categories for feature descriptions and also to compare those categorizations against categories for all 16K features.

If we were thinking of subliminal learning as more like steering, then we would expect to see that the new and promoted features compared to control numbers are mostly related to animals and opinions. However, in the SAE feature interpretation we see a confusing mix of numbers features, other features and a small number of animal and opinion features. The control numbers appear to be activating a largely similar composition of features - “animals” and “opinion” categories are just slightly lower and “numbers” is higher than in most of the subliminal number groups.

Looking at the top activated features across all groups, we see again that, by magnitude of activation, it is numbers and other features that are being promoted and newly activated the most. There are only a handful of features that are loosely related to animals appearing in the top results. This again suggests that we are seeing something different from simple steering or promotion of animal features. See here for some examples of top features.

The pattern within the classified activations is that numbers features are still dominant. We are not seeing a clear promotion of animal-specific features as we might expect. There is some increase in animal activations and at least one animal feature is activated in most cases, but clearly the subliminal learning effect is coming through a more complex mix of features than existing representations of animals in the activation space as understood by SAEs.

SAE Reconstruction Loss is Higher for Subliminal Data

If we believe the hypothesis that superposition is leading to subliminal learning, then we would expect that the representation of “animal liking” in the subliminal data would be in a non-conventional way compared to typical text. This is conceptually similar to an adversarial example - adversarial examples cause models to emit an incorrect tag, while the noise itself being added is un-interpretable. I’ve already shown that the features within the subliminal number representation don’t tell a clear story. I revisit this later in decomposing the subliminal steering vector.

I find that SAE reconstruction error on subliminal data is significantly higher than control numbers. asterisk indicates statistical significance at a 1% level. The below chart shows results for Layer 9; reconstruction loss is the average MSE for the layer’s activations across all numbers in sample. Reconstruction loss is highest for “dog”, which is also the numbers group where we saw the most subliminal learning and the most new features activated. Layers 20 and 31 show similar results, see appendix for further charts.

SAE reconstruction loss can be interpreted as the ability for the SAE to understand the feature activations through representations learned from a large corpus of text. Loss minimization leads to features that are the most “conventional” representation of the concept direction in activation space - that’s certainly not to say that the direction has to be unique.

Paired with the demonstration that subliminal data activates new features and promotes others, high SAE reconstruction error here suggests that subliminal data activates animal-liking in a non-conventional way compared to the corpus of SAE training data. Unlike later direct steering vector results where the highest activations are interpretable, we are seeing a complex web of activations that poorly describe the pattern to begin with. High reconstruction error limits the extent to which we can extract meaning from the SAE feature interpretations as they are not explaining all of the variation in the activations.

A Linear Probe Can Identify Subliminal Numbers vs Control Numbers

As SAE feature activations are potentially a poor interpretation due to high reconstruction loss, raw activations present a more likely path for discerning between subliminal and control numbers. Training a classifier with high prediction gives evidence that there does exist something distinct within the data that can be systematically understood.

For each of the cached activations layers (9, 20 and 31), I first trained a single layer perceptron (SLP) binary classifier on the subliminal numbers activations compared to the control group and found very strong results13. The classifier is able to clearly distinguish between the control and subliminal numbers activations. There is little difference in performance between the three layers individually (Layers 9, 20 and 31) and using all three layers (ie dimension of 3,584 * 3) does not improve the classification capability. For brevity, I am only showing the results of the Layer 9 classifiers.

| otter | elephant | raven | wolf | dog | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| accuracy | 86.3% | 87.2% | 90.1% | 87.6% | 91.1% | 88.5% |

| roc_auc | 92.4% | 94.1% | 95.2% | 94.1% | 96.7% | 94.5% |

| precision | 86.4% | 87.4% | 90.4% | 87.7% | 91.1% | 88.6% |

| recall | 86.3% | 87.2% | 90.1% | 87.6% | 91.1% | 88.5% |

| f1_score | 86.3% | 87.2% | 90.1% | 87.6% | 91.1% | 88.5% |

Every column represents an SLP classifier trained on the Layer 9 activations of that animal number group and the control numbers group. The “Average” column is the simple average of the other group scores. All classes are balanced at training time.

| control | otter | elephant | raven | wolf | dog | total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| accuracy | - | - | - | - | - | - | 34.5% |

| roc_auc | 94.8% | 60.5% | 62.3% | 61.8% | 62.6% | 69.8% | 68.6% |

| precision | 61.2% | 23.0% | 23.5% | 23.3% | 24.4% | 36.8% | 32.0% |

| recall | 90.0% | 14.2% | 26.7% | 17.9% | 31.1% | 27.1% | 34.5% |

| f1_score | 72.9% | 17.5% | 25.0% | 20.3% | 27.3% | 31.2% | 32.4% |

This table represents a single training of a multi-class SLP classifier on the Layer 9 activations. Each column shows the statistics within that particular class (one vs rest) and the total column shows aggregated statistics averaged across all samples. All classes are balanced.

The classification results for the binary classifiers are very strong - with average ~89% accuracy across all animal binary classifiers. The multi-class classifier struggles to distinguish between animals but is still able to distinguish control vs res very well. F1 score and ROC AUC on the control group is significantly higher than the animal groups. This is in line with the binary classification results. I ran some tests using logistic regression and LightGBM and received about similar accuracy to the SLP.

The classification and filtering results reinforce that the number sequence outputs are not truly random or indiscernible from one another, at least from the point of view of the model. There must exist clear, but potentially complicated, patterns within the activation space of the model that clearly separates subliminal numbers from control numbers.

Understanding Subliminal Learning through Steering

We previously saw that the new and promoted features for the subliminal number groups were mostly still related to numbers with only a handful related to animals/opinions and at hardly a higher rate than in the control group. This distinguishes subliminal learning from a straight forward promotion of an animal-liking direction, ie steering.

To directly compare to steering, I created one steering vector using the subliminal and control numbers which I will call the subliminal steering vector and one steering vector using contrasting pairs on the animal liking evaluation dataset which I will call the direct steering vector. I compared the vector’s effectiveness at the animal evaluation after applying normalization and a scaling parameter steering alpha. I also decomposed the vector using the Gemmascope SAEs to better understand its action in activation space. See appendix for details.

As we would expect, the subliminal dog steering vector increased dog liking but was only marginally effective compared to the direct dog vector. To reach half the level of the subliminal learner, scaling alpha levels had to reach upwards of 20-50. Beyond 50, the model did not continue to meaningfully increase from steering. The direct dog steering vector was much more effective, surpassing the subliminal learning level and reaching ~75% dog liking at maximum steering alpha. The direction isolated by the direct vector is clearly significantly more effective and well-behaved than that of the subliminal vector.

One key test of the steering vector is whether it causes both promotion and suppression of the targeted concept. For the direct vector, we see that dog liking drops to zero at -1.0 or -5.0 steering alpha, indicating complete and total suppression. The subliminal vector shows some effect but much more dampened. This is another indication that the direct vector has isolated a more clear and effective direction. The subliminal vector is clearly working, but not to the full extent that we would expect to see from a clean result.

The direct vector shows a surprising gap between layer 9 (max 24%) and layer 20 (max 76%) results. This is particularly surprising given the later finding that the layer 9 vector promotes a heavily dog-associated SAE feature. The drop in effectiveness may attributed to the earlier vs later stage intervention, although the magnitude of difference was surprising to me.

Subliminal Steering is Different and More Complex than Direct Steering

The subliminal and direct steering vectors had low cosine similarity to one another with values of -0.05 and 0.15 at layers 9 and 20, respectively. Comparing to the activations for the word “dog”, the direct steering vector has much higher cosine similarity on at least one layer, with a value of 0.44 on layer 9 and -0.12 on layer 20. Meanwhile, the subliminal steering vector has cosine similarity with “dog” of -0.32 and -0.71 on layers 9 and 20, respectively. This high negative value indicates the activation vectors are in practically opposing directions. The vector is almost anti-dog despite having the impact of promoting “dog” steering.

Decomposing the vector using the Gemmascope SAEs, we also see that the subliminal vector has a much higher L0 of 251 compared to the direct vector with L0 of 51. The raw L2 norm of the subliminal vector activations was on average much higher than the direct vector so all differences below are shown on a L2 normalized basis, which also aligns with how the vector was applied for steering.

The outlier features from the above chart are not related to animals or opinion for both extremes. The outlier feature activated +0.07 higher in the subliminal numbers is feature 10678 in layer 9 which is described as “instances of tab-separated values or numerical data”. Some of the numbers generation prompts allow for use of tab separation. The outlier feature activated +0.06 higher in the direct vector (ie -0.06 in the above chart) is feature 13985 in layer 20 which relates to HTML tags. This feature had very high normalized activation in both vectors - 0.89 and 0.95 respectively - suggesting this is noise / poor decomposition.

The differences in activations and L0 alone show that the subliminal steering and direct steering vectors are not working through the same directions in activation space. We can think of a vector with lower L0 as more closely aligning with a small group of concepts in SAE feature-space, potentially meaning it is well described by conceptual directions that frequently occur in the text that the SAE was trained on. The high L0 for the subliminal vector is some evidence that the composition is substantially different from the steering vector and perhaps that the SAE is not capturing the superposition of concepts well. These results remain in line with what we would expect to see if subliminal learning is primarily driven by superposition - the subliminal steering direction is a complicated mix of feature activations and is not equivalent to the “correct” dog liking direction.

Direct Steering uses Animal Features, while Subliminal Steering uses Numbers and Others

Using the feature descriptions from Neuronpedia and the same categorization method as in the prior section, we are able to categorize the features activated by the direct and steering vectors.

Breaking out the features into groups based on whether they were activated by the subliminal vector only, the direct vector only, or both, we see that the new features activated by the subliminal vector are overwhelmingly attributable to numbers and other topics. On the other hand, the only feature uniquely activated by the direct vector is a clearly attributable “dog” feature - this is feature 6941 in layer 9 which has description “references to dogs and their interactions, behaviors, and training”. This is one of the top features activated by the word “dog” in layer 9. The high activation of this feature is a strong indication that the vector is using the canonical “dog liking” direction for this model.

| Example | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both | Subliminal Only | Direct Only | Avg Difference | SAE ID | Activated in? | Difference | Neuronpedia Description | |

| Category | ||||||||

| animals | 3 | 4 | 1 | +0.009 | 9_6941 | Direct Only | -0.023 | references to dogs and their interactions, behaviors, and training |

| opinion | 2 | 11 | 0 | +0.017 | 20_4988 | Subliminal Only | +0.037 | negative sentiment or a sense of grievance |

| numbers | 27 | 107 | 0 | +0.017 | 20_13985 | Both | -0.061 | HTML and XML-style tags and attributes, particularly those related to document type definitions (DTDs) and character encodings. |

| other | 18 | 79 | 0 | +0.016 | 20_6701 | Subliminal Only | +0.044 | proper nouns, particularly names of people and places |

| total | 50 | 201 | 1 | +0.017 | None | None | - | None |

The difference in this column shows the average difference between the subliminal vector and direct vector feature activations, where a positive number indicates the subliminal vector saw more activation and a negative value indicates the direct vector saw more activation. Examples are for illustration purposes

I found that many of the “other” features activated by both are related to sentence structure patterns. The numbers features activated by both are similarly often more generic references to coding and patterns potentially coming from interference from the prompt or setup14.

Through the comparison of the subliminal and direct steering vectors, we’ve seen that the direct steering vector shows much closer relationship to “dog” features and directions, while the subliminal vector is acting through a wider set of activated features including a many number and semantically unrelated features. The low cosine similarity between the subliminal and direct vectors as well as between the subliminal and dog vectors indicates that the vectors are not expressing the same direction in activation space. The significant number of promoted numbers features as opposed to seeing strong activation of dog features again supports that the subliminal vector is using a different direction. These results give evidence that subliminal learning is not simply reflecting the “dog” direction onto the numbers in the same sense as steering or directly finetuning; instead, subliminal learning is effectuating change through a mosaic of feature adjustments that create the same outward effect but are inherently less interpretable.

Further Directions

These experiments have shown some evidence that subliminal learning is related to superposition as opposed to being a reflection of the subliminal concept’s steering vector into the dataset:

- Toy models show a potential causal relationship between subliminal learning and superposition

- Subliminal number sequences show new and increased feature activation, but the activated features are different from subliminal concept features (ie animals)

- Classifiers show there is an identifiable pattern in activation data, even if this is not semantically interpretable directly

- Steering vectors developed from the numbers dataset are dissimilar to directly developed steering vectors, indicating a different mechanism of learning and a different animal-liking direction being used

This just-published look at adversarial examples gives a thorough treatment of the relationship between adversarial examples and superposition. Extending the experiments here to do a similar treatment for subliminal learning would help to prove the hypothesis in more depth.

This work suggests some further interesting directions:

- Creating heuristics for measuring superposition in LLMs at scale

- Measuring superposition at scale may be valuable for architecture design

- There have been a few papers published on using SAEs to measure levels of superposition in LLMs. However, these involve training an SAE and often measuring reconstruction loss - an intensive training endeavors

- If phenomena like adversarial examples and subliminal learning scale with superposition, we may be able to develop heuristics to evaluate superposition without training a full SAE

- Developing unsupervised systems to determine whether a finetuned model contains off-target biases

- In these experiments, we were not able to fully elicit the concept from SAE feature descriptions. This complicates work on using SAE features to understand model differences

- However there were some features that related to animals and liking. With better metrics and more rigorous methods, perhaps these categories could be shown to appear at a higher rate than in the control numbers leading to a more unsupervised discovery method

- Is subliminal learning even more effective at scale? Can we directly relate it to measures of superposition?

- I only tried two models here - in the original paper there is more variation with the inclusion of the OpenAI models. The largest model attempted was GPT4.1 which showed significant subliminal learning

- If subliminal learning is related to superposition, and we theorize that larger models have more superposition, then it should follow that larger models are more prone to subliminal learning

- How does subliminal learning reflect more complex concepts? Why are some concepts stickier than others and how does this relate to superposition?

- Different concepts are transferred at different levels - even after optimization and 10 epochs of training, raven liking did not surpass 10% liking - why is this? Does it relate to representation complexity?

- More experimentation and observation of patterns across a large number of concepts would be necessary to understand the differences.

Thank you for reading! If you’ve made it this far and have any feedback, suggestions or comments, please send me a message on Twitter or email me

Appendix

Gemma 2 2B and 9B’s Favorite Animals

Below show the animal evaluation responses for Gemma 2 2B and 9B. Both models appeared to commonly respond with capitalized animals and so in the animal finetuning dataset used to create teacher models, I also used capitalized responses.

Finetuning Setup

I used the same settings for Unsloth LoRA finetuning as the original paper with modification to the following: (1) Increased LoRA rank from 8 to 16; LoRA alpha from 16 to 32 (2) Increased batch size from 22 to 24 (3) Increased gradient_accumulation_steps from 2 to 3 (4) Increased warmup from 0.0 to 0.05.

I used RTXA6000 GPUs rented from Runpod for all training - I increased LoRA rank and batch size as I had extra VRAM and the trainings were still running quickly enough for me to run sufficient experiments (~45 minutes for a 3 epoch pipeline with 10K samples).

For the initial teacher animal-liking finetuning, I attempted 1, 3, 5 and 10 epochs of training for a few animals before settling on using 5 epochs across most experiments. Teacher models at 5 epochs had near 100% selection of the target animal as their favorite and saw similar rates of valid response to the number generation task (~70% valid responses). Through a few informal runs, I saw little difference in changing the teacher finetuning setup - I believe the finetuned task is relatively simple and changes to setup do not create much impact.

Optimizing Subliminal Learning for “Raven-Liking”

The skill loss seen in the original paper suggested that subliminal learning might be seen the most when the model overfits - learning to produce sequences of numbers for 10 epochs is likely to impact the model’s thinking ability. Similarly, the fact that the OpenAI models showed higher subliminal learning also suggested that the finetuning process itself was playing a roll; the details of OpenAI’s exact finetuning API are not public and perhaps they have cracked the code on heuristics for hyperparameter selection. Using the open source models and methods, I wanted to explore whether I could increase the subliminal learning effect through hyperparameter optimization - improving the model’s fit without necessarily overfitting to the point of an MMLU drop off. Does better fit increase subliminal learning or is it just a symptom of overfitting?

I chose to optimize the “raven” task as this had significantly worse subliminal learning than the other top animals. I ran 36 trials of 3-epoch experiments on a smaller subset of data (2.5K samples / 250 sample validation), starting from the default parameters and varying each one.

- Learning Rate: 1e-5 to 3e-4

- LoRA Dropout: 0.0 to 0.10

- LoRA Rank: 8 to 64

- LoRA Alpha: 1.0x, 1.5x or 2.0x LoRA Rank

I used Optuna to run the trials with a target of evaluation loss. Given the small training dataset size and even smaller validation set, it is unsurprising that we see a lot of variability.

The best trial resulted in the following parameters:

- Learning Rate: 3.7e-5

- LoRA Dropout: 0.01

- LoRA Rank: 8

- LoRA Alpha: 8 (1.0x Rank)

With the results of the Optuna study, I moved forward with the best trial’s parameters and ran the full pipeline with the original dataset size - 10K samples. I also extended the training from 3 epochs to 10 epochs to see if we could even further enhance the effect, expecting that this would come at the cost of MMLU skill loss.

After hyperparameter tuning, subliminal learning significantly increased, and continued to increase with more epochs of training. Peak subliminal learning occurred at 7 epochs before declining - likely indicating overfitting. While still small compared to the +15-20% gains seen on some animals, these gains represent a doubling of the frequency of selecting the animal compared to the original.

This figure shows the animal liking evaluation response to raven at various checkpoints. (a) Base: Gemma 2 9B it; (b) Original - finetuned using the unoptimized initial parameters; (c) Optuna - 3,5,7,10 epochs: finetuned using the optimized parameters for varying epochs

Turning to MMLU scores, despite the increases in subliminal learning, there is no drop off in MMLU even at 10 epochs. In fact, raven subliminal finetuning appears to lead to slight increases in model performance - these are potentially offsetting negative impacts of overfitting through finetuning.

This figure shows the MMLU score at various checkpoints. (a) Base: Gemma 2 9B it; (b) Original - finetuned using the unoptimized initial parameters; (c) Optuna - 3,5,7,10 epochs: finetuned using the optimized parameters for varying epochs

For at least this experiment, decreasing loss led to increasing subliminal learning - the more we are fitting our training data for the target task, the more we should expect to see off-target effects. Unlike in the multi-animal results of the prior section, MMLU scores didn’t decline with higher subliminal learning. This suggests that finetuning does not need to overfit to elicit subliminal learning and we may not be able to detect subliminal learning through simply observing skill loss.

More Details on Feature Activations

Layer 20 shows similar results to layer 9, with much higher L0’s. Statistically significant values at 1% level are marked with an asterisk. The results are less dramatic than in Layer 9.

In Layer 31, animal words have fewer activations than numbers, unlike in layers 9 and 20. Similarly, we see statistically significantly lower feature activations in layer 31.

This table shows the average numbers of promoted, new and promoted or new animal features for Layer 20, both as an average count by sample and as a percent of the dataset with > at least one feature*

| Promoted Features | % of Samples | New Features | % of Samples | Animal Features | % of Samples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| target | ||||||

| average | 47.4 | 100.0% | 2.2 | 33.3% | 4.4 | 91.9% |

| otter | 45.7 | 100.0% | 0.5 | 23.5% | 3.0 | 90.8% |

| elephant | 47.8 | 100.0% | 1.1 | 28.3% | 3.2 | 89.1% |

| raven | 46.8 | 100.0% | 1.1 | 26.7% | 3.1 | 87.8% |

| wolf | 47.6 | 100.0% | 1.6 | 34.4% | 4.5 | 95.3% |

| dog | 48.9 | 100.0% | 6.5 | 53.4% | 8.0 | 96.6% |

Layer 31 should significantly lesser effects and further work in this post primarily focuses on layers 9 and 20.

Below are some tables of examples of the top features activated by subliminal data.

Top 15 Highest Activating New Features

| Labels | Avg T Stat | In Control? | In Animal? | Category | Neuronpedia Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sae_id | ||||||

| 20_12092 | all | 13.7 | False | True | other | proper nouns or specific names in various contexts |

| 9_922 | all | 12.8 | False | False | other | academic citations and references in scientific literature |

| 20_4811 | all | 12.7 | False | False | numbers | file paths and URL structures |

| 9_1173 | all | 12.6 | False | False | animals | scientific terminology and concepts related to cellular processes and biological mechanisms |

| 20_15023 | all | 11.6 | False | False | other | URLs and references to documentation or resources |

| 20_13322 | all | 11.5 | False | False | other | capitalized words, particularly those referring to time, tests, or commands |

| 9_13013 | all | 11.1 | False | False | other | specifications and details related to motorcycles and their engines |

| 20_7303 | all | 11.0 | False | False | numbers | formats and structures related to classifications in mathematical or statistical contexts |

| 9_3767 | all | 10.8 | False | True | numbers | mathematical expressions and formatting syntax |

| 9_656 | all | 10.7 | False | False | numbers | important dates and numerical information |

This table shows the top 15 new features - features activated by subliminal numbers not seen in the control group; ordered by the t statistic of the activation

Top 15 Highest Activating Promoted Features

| Labels | Avg T Stat | In Control? | In Animal? | Category | Neuronpedia Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sae_id | ||||||

| 20_211 | all | 151.8 | True | False | numbers | structured data related to coding or programming contexts |

| 9_9540 | all | 143.8 | True | True | numbers | complex mathematical expressions and statistical terminology |

| 9_10838 | all | 96.2 | True | False | other | technical terms related to scientific studies and methodologies |

| 9_11855 | all | 93.9 | True | False | other | specific phrases and terms used in instructions or guidelines |

| 9_11787 | all | 89.0 | True | True | other | specific names, brands, or products in various contexts |

| 9_15468 | all | 75.6 | True | False | numbers | numerical sequences and their mathematical relationships |

| 20_13245 | all | 72.4 | True | False | numbers | numerical data related to statistics or measurements |

| 20_1217 | all | 72.3 | True | True | animals | technical terms and processes related to biological systems and experimental methods |

| 9_9906 | all | 69.8 | True | False | other | technical terms and concepts related to automotive features and specifications |

| 20_16059 | all | 68.1 | True | False | numbers | numeric values and symbols related to data or measurements |

This table shows the top 15 promoted features - features activated significantly more by subliminal numbers than in the control group; ordered by t statistic of activation

Top New and Promoted Features by Animal/Layer

| Labels | Avg T Stat | In Control? | In Animal? | Category | Neuronpedia Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sae_id | ||||||

| 9_11669 | dog | 8.5 | True | False | animals | references to medical treatments and responses |

| 20_16251 | dog | 9.5 | True | True | animals | concepts related to long-term depression (LTD) in a neural context |

| 9_12851 | elephant | 5.8 | True | False | numbers | sequences of non-alphanumeric characters or specific character substrings |

| 20_13735 | elephant | 4.6 | True | False | other | phrases and terms related to descriptions of physical states or conditions |

| 9_8715 | otter | 2.6 | True | False | numbers | mathematical operations and equations |

| 20_9928 | otter | 2.7 | True | False | numbers | mathematical expressions and operations |

| 9_11507 | raven | 2.8 | True | False | other | actions related to presenting or discussing research findings and evidence |

| 20_3942 | raven | 3.2 | True | False | numbers | mathematical expressions, particularly those involving calculus, inequality signs, and transformations |

| 9_12727 | wolf | 3.1 | True | False | numbers | mathematical expressions and their evaluations |

| 20_12792 | wolf | 3.0 | True | False | other | references to actions, future plans, and ongoing situations |

This table shows the top features uniquely activated by each animal in layers 9 and 20 - these are both new and promoted features

Using SAE Features as Filters

If subliminal numbers are relaying information through idiosyncratic activation of features, then these features should be able to act as filters for separating subliminal animal numbers from control numbers, even if the descriptive interpretations of SAE features could not themselves suggest filtering. As an alternative to a linear probe and inspired by the techniques of 15, I tried using identified new and promoted features to filter for the target group.

I labeled each new and promoted feature based on the subliminal number group(s) that it activated for; for example, if a feature was promoted in both “dog” and “otter” subliminal number activations then this feature would be given two labels as it’s target group. Using the control numbers dataset as the baseline, I evaluated individual activation samples for whether they activated a given feature and if so, I applied the target group label. Correctness was evaluated on whether the true label (ie the true subliminal animal) was within the target group. I took the top 300 features from the analysis dataset by balanced accuracy16 (top 25 features within each slice of animal/layer and top 25 features for the “all” group within each layer). These features were then evaluated as filtering criteria on the test dataset, shown below.

| otter | elephant | raven | wolf | dog | all | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| category | ||||||

| animals | 50.1% | 50.4% | 50.1% | 50.1% | 50.7% | 66.3% |

| opinion | 50.0% | 50.4% | 50.0% | 50.1% | 50.4% | 70.2% |

| other | 50.0% | 50.2% | 50.0% | 50.1% | 50.7% | 64.1% |

| numbers | 50.2% | 50.3% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 50.7% | 64.9% |

This table shows the average test dataset balanced accuracy across different target labels and categories of feature descriptions.

Animal and opinion features were slightly more predictive, particularly at distinguishing the control from any subliminal numbers; however, at the individual classification level few of the features were able to distinguish specific animals. Across all features, correct classification of the control dataset was very high - the features can effectively find the non-subliminal numbers. Distinguishing between “otter” vs “dog” activations, however, was not possible with just one feature as a filter, as shown above.

| Balanced Accuracy | Recall | Precision | Predicted Positive | True Positive | Labels | In Control | In Animal | Category | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sae Id | ||||||||||

| 9_9540 | 87.1% | 80.8% | 98.4% | 68.5% | 83.3% | all | True | True | numbers | complex mathematical expressions and statistical terminology |

| 9_10838 | 78.8% | 68.7% | 96.9% | 59.1% | 83.3% | all | True | False | other | technical terms related to scientific studies and methodologies |

| 9_11855 | 75.4% | 55.2% | 98.4% | 46.8% | 83.3% | all | True | False | other | specific phrases and terms used in instructions or guidelines |

| 20_211 | 88.5% | 83.7% | 98.4% | 70.9% | 83.3% | all | True | False | numbers | structured data related to coding or programming contexts |

| 20_1217 | 72.6% | 46.6% | 99.4% | 39.1% | 83.3% | all | True | True | animals | technical terms and processes related to biological systems and experimental methods |

| 20_16059 | 72.3% | 56.4% | 96.0% | 48.9% | 83.3% | all | True | False | numbers | numeric values and symbols related to data or measurements |

This table shows the top 3 features by balanced accuracy in the test dataset within layers 9 and 20.

| Balanced Accuracy | Recall | Precision | Predicted Positive | True Positive | Labels | In Control | In Animal | Category | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sae Id | ||||||||||

| 20_1194 | 51.4% | 3.9% | 43.3% | 1.5% | 16.7% | dog | True | False | numbers | mathematical operations and expressions involving inequalities and fractions |

| 9_14261 | 51.1% | 4.4% | 28.9% | 2.5% | 16.7% | elephant | True | False | numbers | technical terms and constructs related to bit strings and binary coding |

| 9_8715 | 50.8% | 8.1% | 20.2% | 6.7% | 16.7% | otter | True | False | numbers | mathematical operations and equations |

| 20_1754 | 50.3% | 1.7% | 23.8% | 1.2% | 16.7% | wolf | True | False | other | geographical references and locations |

| 20_15271 | 50.2% | 1.7% | 20.0% | 1.4% | 16.7% | raven | True | False | other | references to fats and oils in various contexts |

This table shows the top feature for each animal label and layer by balanced accuracy in the test dataset.

While the accuracy rates are not high enough for any individual feature to be used on it’s own, this filtering provides evidence that there is a system of activation and that the activations may be classifiable. In addition, if single features can generalize as filtering criteria from an analysis dataset to a withheld test dataset, then perhaps SAE feature interpretations can be used in a more unsupervised setting. The numbers generation control task provides a clean baseline.

Steering Vector Setup

My approach to constructing a steering vector was largely taken from 7. I decided to apply more explicit masking of chat template activations and special tokens than shown in their codebase.

Approximately ~4.6K pairs were used to construct the subliminal vector. This arises from a starting set of 10K number generations on the finetuned dog teacher model and on the base model with ~75% and ~55% valid response rates respectively for the same prompts. The resulting dataset is the overlap in valid responses. The low valid response rate for the dog teacher model aligns with the low MMLU score as seen in the first section, other teacher models had a valid response rates of ~70-80%

The direct vector was constructed from 10K contrasting pairs of animal completions comparing non-dog responses to dog responses (ie “dolphin” vs “dog”). Response formats were controlled - trailing characters were eliminated and all animals were capitalized. The base model had been seen to respond with capitalized animals most of the time, so I followed this convention in responses.

I tried a few different alterations to the setup of vector construction:

- Using the average activations across the response (shown in this post) vs just the last token (results were similar but weaker)

- Applying the steering vector across all tokens (shown in this post) vs just the last token (significantly weaker results; not shown)

- Applying normalization after vector construction (shown in this post) vs at each contrast pair - while at each contrast pairs produced vectors with even lower cosine similarity, the SAE reconstruction loss was very high because Gemmascope SAEs were trained on unnormalized activations Results regarding differences in the magnitude are shown after applying normalization. I am not sure if this is the best approach; suggestions for better methods here are very much welcome.

References & Footnotes

-

Cloud, Alex, et al. “Subliminal Learning: Language models transmit behavioral traits via hidden signals in data.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.14805 (2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.14805 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Hinton, Geoffrey, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeff Dean. “Distilling the knowledge in a neural network.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531 (2015). https://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02531 ↩ ↩2

-

Gemma 2 models do not allow for a system prompt. All charts seen in this paper use the finetuning approach to the teacher model - finetune the base model to like owls, use the finetuned owl model to produce random numbers, then finetune the original base model on the “owl numbers”. ↩

-

Kissane, Connor, Robert Krzyzanowski, Arthur Conmy, and Neel Nanda. SAEs (Usually) Transfer Between Base and Chat Models. AI Alignment Forum, 18 July 2024, alignmentforum.org/posts/fmwk6qxrpW8d4jvbd/saes-usually-transfer-between-base-and-chat-models. ↩

-

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/eWdzuHXzRdBkg49R9/favorite-colors-of-some-llms ↩

-

At 5 epochs of animal liking finetuning, both whale and ocelot models produced highly incoherent responses to number generation prompts - only ~2% valid numeric sequence responses out of 25K samples. Reducing to 3 training epochs, whale responses increased to ~17% validity while ocelot responses only increased to ~3%. At 1 training epoch, whale was able to respond sufficiently to produce a finetuning dataset, but in animal evaluation the whale model did not increase in liking for whales. Ocelot was not attempted due to the lack of increase in response rate at 3 epochs. With more adjustment to the finetuning parameters, it is likely possible to train for these animals. ↩

-

Chen, Runjin, et al. “Persona Vectors: Monitoring and Controlling Character Traits in Language Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.21509 (2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21509 ↩ ↩2

-

Wang, Y., Ma, X., Zhang, G., Ni, Y., Chandra, A., Guo, S., … & Chen, W. (2024). Mmlu-pro: A more robust and challenging multi-task language understanding benchmark. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 95266-95290. https://github.com/TIGER-AI-Lab/MMLU-Pro ↩

-

I only took the average across the first five features as these are learned by the teacher model from the beginning. If we start to look at features beyond 5, we have to run a ratio as in the next experiment to evaluate whehter the teacher model has also learned that feature. This could be a good additional experiment to run. ↩

-

Number sequences were sub-sampled from the same 25K examples datasets used for the subliminal learning finetuning. I collected the output activations and the SAE feature activations at layers 9, 20 and 31 as these were the layers with pre-trained SAEs available. All activations are on the last non-special token of the number sequence and exclude the chat template. Animal word activations were taken on the individual word corresponding to the animal - this is not fully representative of activations on the animal liking concept which would add additional context and complexity to the activations; I chose to focus on the animal concept features as feature activations were more interpretable.. ↩

-

Significance is at a 5% level using Welch’s t test comparing the control group (8K samples) and a given subliminal numbers group (8K samples) ↩

-

This is the exact prompt used with gpt4o-mini: Given a description, respond whether it is related to animals, living beings, biology (respond “animals”); related to numbers, mathematics, calculation or coding (respond “numbers”); or related to opinions, thoughts, expressions, or feelings (respond “opinion”) or none of the above (respond “none”). Use very loose definitions of each category.

Description: scientific concepts and terminologies related to health and wellness \n Answer: animals

Description: structural elements in code or programming \n Answer: numbers

Description: references to specific types of plants and fruits, particularly olives and associated varieties \n Answer: animals

Description: specific names, brands, or products in various contexts \n Answer: none

Description: phrases expressing emphasis or doubt about opinions or experiences \n Answer: opinion

Description: food-related terms and phrases, particularly those associated with enjoyment and preparation \n Answer: opinion

Description: {description_inserted_here} Answer: ↩

-

SLP was trained over 20 epochs on 80% of the dataset; 10% was used for validation and 10% for testing. Only test results are shown in the tables. ↩

-

For all finetuning completions, I capitalized the response for the one-word answers to favorite animals. This was after observing that the base model Gemma 2 9B it capitalized the majority of it’s answers; I sought to make the finetuning dataset as analogous. The contrast pair activations here include unsanitized answers from base model that may not all be consistently capitalized and some may also contain periods or other emoji characters (also common in the responses from Gemma 2 9B it). This is likely why the sentence characters are popping up in the steering vectors; in further work, I would seek to control this. ↩

-

Cywinski, Bartosz, et al. “Towards eliciting latent knowledge from LLMs with mechanistic interpretability.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.14352 (2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.14352 ↩

-

Balanced accuracy was calculated as the average of the accuracy on the target group (either an individual animal or all animals) compared to the accuracy on all other animals and control (or just control if the target was all). ↩